by A.K. Sykora.

by A.K. Sykora.

“Our children live in France,” plump Algernon volunteered.

Snug at her faux-marble desk, the heavy-shouldered director studied him. “Have they been notified?”

“Yes, I called the twins as soon as poor Mildred got certified.”

“And you?”

“I didn’t want to leave her,” he said blandly. “We’ve been married thirty-two years.” Hunched on the bench beside him, Mildred studied the ceiling’s lo-burn bulb, and her silvery mouthpatch twitched.

“You’re very generous, Mr. Shipley. Few adults arrive at the home attended. Mildred, you should be grateful.”

The gaunt, grey-haired prisoner made a choking noise.

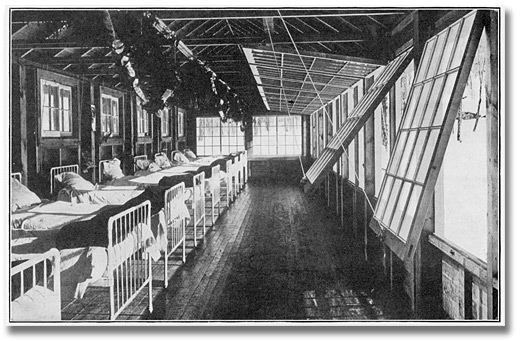

Image from here.

“You can take that off during private time,” Algernon reminded his wife, who pulled off her mouthpatch and threw it on the floor:

“A fine mess you got us into.”

“You’re the one who got certified,” he said mildly. He patted her shoulder and she shrugged away. “Let me give you a hand with your luggage.”

“I’d rather unpack my own things.” Mildred glared around at the flimsy rowhouse.

“Very well; take your time.” He arranged his pedigree dogs on a shelf, then tidied his clothes into the smaller wardrobe, whose knob fell off.

“For the money you’d think we’d get a better knob.”

“The place is a scam, don’t you see?”

“You’re not supposed to express opinions, Mildy.”

“I’ll bloody well–”

“Amazing grace…” warbled a female voice. The door buzzed, and he hurried to open it.

“Good afternoon,” cried a middle-aged nurse in a soiled, half-caped uniform, her hair pulled back into a listing bun. “I’m Hannah-E, your sector nurse, with your coupons for September. Any problems on your first day?” Mildred held her tongue.

“Everything’s brilliant,” said Algernon, “except we lost our knob.”

Hannah-E popped the wardrobe open with her fingers. “I can report this to maintenance, but a new one will fall off too.”

“Never mind,” he said cheerfully. “We’ll open it just like you showed us.”

#

While Algernon went on a guided tour, Mildred plucked at weeds in their pocket garden. Abruptly the man parked in a chair next door lurched to his feet:

“Howdy, I’m Frank Zell.” He stuck his furry hand over the straggling hedge. His lips looked loose, disreputable.

“Mildred Shipley,” she said crisply, shaking the end of his fingers. “Pleased to meet you.”

“What are you in for, Milly?”

“Chronic irritability.” She lifted her chin. “I was a teacher of maths and intelligent consumption, in London. I veered from the approved syllabus.”

“I’ve never been approved anywhere. I was a jazz musician.”

Her eyes widened. “How long have you been–confined?”

“Eleven years.” He scratched his drooping belly, and she wrinkled her nose.

“Are there any youngsters in the home? We didn’t see any, driving in.”

“They’re all housed together, in the noisy sector.”

“Just as well, I suppose.”

“Milly, you’re educated. Can you help with my tax returns?” From his pocket he pulled a rumpled lump–chocolate.

Shuddering, she whispered, “Is that real?”

“Sure.” He winked and slid it back into his pocket. “Don’t tell your husband.”

“I don’t know if I’ll have time to help you.”

Frank guffawed and scratched his belly. “We’ve got all the time in the world.”

“I plan on getting out of here,” she declared.

“Three meals a day and clean sheets: that’s better than most people get outside. And the nurses leave us alone if we keep to ourselves.” He pointed at a streetlight’s rusted camera. “It’s broken, just a scarecrow.”

#

Whenever she visited Frank on Tuesday and Friday afternoons, bosomy Nurse Angelina-O wore white, fishnet stockings. Her treatments rattled Algernon’s china dogs, and when she left, her handbag bulged (with contraband, Mildred supposed). Frank fed a woolly dog named Gig, who chased birds and squirrels in Peppermint Lane and sometimes wailed at night like a hungry baby.

One afternoon Algernon was weaving potholders at the activity pavilion with his friends, when the cries and thumpings from next door drove Mildred from the house. She chose a path into the woods, walking briskly past several cameras in the trees. She couldn’t infect anyone with her discontent. The nurses would leave her alone.

She heard Gig barking frantically, and a rabbit bounced across the path. As she brandished her umbrella at the dog, the rabbit gave an agonized cry, and yellow sparks shivered from the undergrowth. Mildred smacked Gig on the back, and he turned tail, whimpering.

An electrified fence? Squinting, she made out the wire bands strung on mossy posts. She’d climb to higher ground, and claim that she’d trailed a black-tailed godwit. The sun hung low, and soon Hannah-E’s tricycle would stop in Peppermint Lane with styropor boxes of chicken vindaloo.

Mildred climbed a narrow path, which ended at the sign, Trespassers Will Be Cloned.

Mischievously she pulled the sign off the gate and threw it on the ground. She rattled the gate–locked. Someone had snipped the fence, though, so she bent out some wires and wiggled through. Beyond a hill of rotting tires she found a cinderblock weather station, a three-cup anemometer still twirling on its collapsing roof. The padlocked door bore a rude graffito about Angelina-O. Bending over like a wary soldier, Mildred stepped towards a stone parapet.

She peered over and gasped at the sheer drop down. The fence beyond zigzagged through twilit woods, dipping east towards a loopy river. The assembly hall’s steeple loomed in the west, with its clock that always read 12:30, and giant machines crept over rolling farmland in the distance. The lights twinkling on the horizon must be Rottenboro.

Suddenly an electric bass’s deep thumpa-thump burst from the noisy quarter, and moments later black smoke flared. Hannah-E had explained the youngsters sometimes burned their garbage for sport. Maybe they were vandalizing their living quarters this evening.

Spying a manicopter, Mildred crouched in the prickly weeds. He rose towards the Hall, his legs splayed behind, his backpack’s rotor whirring like a distant kitchen mixer. What if Algernon got home early? Hannah-E would ask about her. What if they thought she’d run away?

#

“Where have you been?” Algernon asked, who’d poured himself a glass of nutri-milk.

“I took a walk in the woods and lost track of the time. They won’t give us watch batteries, you know.”

“Mildy, I do wish you’d wear your patch and participate in the activities. There’s a bird-watching walk on Friday. Didn’t you used to watch the birds?”

Shrugging, she sat down at the table. “What’s this paper here?”

“Our permanent acceptance.”

“But I want to leave.”

“How?” he chided. “When you won’t even take your medications. You’ll never be decertified, Mildy. This way at least we’ll have security, and always be together.” She rolled her eyes. “There’s a graveyard next to the chapel of remembrance, so the twins won’t have to ship us back to Little Pecker.”

“What about our house? Our mini-car?”

“The nurses will take care of everything.”

“What do the nurses know?”

“Can’t you make an effort to fit in, Mildy? You’d be so much happier.”

She scrambled into the bedroom and banged the door, and he heard her weeping in dry gasps.

#

Mildred lay rigid, listening to his even snoring. The nerve of the man–signing away their assets. Next, he’d be sneaking sweets into her food; she’d overheard Hannah-E suggesting it.

Why wait for them to pacify her? She’d dig under the fence, near the riverbank, and wade or swim across. She’d hike through the fields and head for Rottenboro. No one expected her to try. “Lights out” at the home meant none at all. But she’d hidden her flashlight in her wardrobe, instead of turning it in.

Moving softly, she dressed, and stuffed a bread pack into a bag, with three cartons of nutri-milk. Algernon groaned in bed. She scribbled a note she left on the table: “Dear, I can’t stay in this awful place. Don’t forget to brush your dentures.”

Warily she made her way to the woods. The stars shone down like greedy eyes. Suddenly a shaggy thing bumped her. “Get away!” she cried, and Gig barked at her, and dodged a swipe of her shovel. When he chased her, nipping at her calves, she threw it at him and he yelped and fled.

Suddenly blades beat overhead, and a white light came slicing through the trees, as a dull, meccano-voice boomed:

“Freeze–or be erased, all your data burned.”

Far away, Algy cried pitifully, “Mildy, don’t leave me,” and Angelina-O whooped, “Algae and Mildew have gotten loose!”

Blundering into the fence, Mildred followed it, climbing steadily, whipped by branches. A manicopter holding a searchlight swooped: whump, whump, whump.

“Mildred, stop–or be erased!” She wriggled through the fence at the weather station, ran gasping up the last switchback and staggered towards the parapet.

“The hell with you all!” she shouted and jumped. The air seemed to thicken though, slowing her plunge to a crawl. The stars danced in indolent circles, and she smelled the tang of pine. Somewhere behind her Algernon bleated:

“Mildy, do come home.”

“Still hanging on?” she yelled, and slammed the ground.

#

Rows of candles shimmered at the assembly hall’s business end. Flanking the aisle like spread wings, nurses in white robes sang together, “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” to the tune of “God Save the Queen.” Reverend Chalkbottom stooped at the podium, a sorrowful vulture, his bald crown reflecting the lo-burn spotlight:

“Not many of us knew Mildred Shipley. She was a small and retiring soul, a wallflower here at the Briarcliff Home for the Chronically Irate….”

Standing next to a big and musty nurse, she shouted: “You fool, I’m still alive!” Her voice seemed a squeak, however, and on he droned, like a sleepy bagpipe.

“It’s so chilly today,” the big nurse whispered to a littler one.

“I thought they’d repaired the furnace,” she replied, and Mildred poked her in the ribs. Her hand slipped through the pew.

Why wait for the conclusion of her own, ridiculous funeral? Mildred’s running feet made no noise on the marble, or the paving stones outside. Her body felt light and thin, without hunger. If I’m dead I can get through that fence, she thought.

For the first time, though, she felt curious about the home’s other inhabitants.

#

“The youngsters are rioting because we’re out of cell-phone batteries again.” The director crossed her heavy legs. Mildred perched on the edge of her faux-marble desk, and the blinds hung open. Black smoke rose in streams from the noisy quarter.

“What shall we do?” asked Hannah-E.

“Send up another manicopter. Spray them with psychotropic drugs.”

“At once.” The nurse hurried off, almost bumping into Algernon.

“May I speak with you?” he appealed to the director, who flashed him a chilly smile:

“I’m rather busy, as you see, but you’ve always been so well-behaved. If more citizens shared your qualities, we’d have no need for the nation state.”

“My director,” he cooed, and offered her a straggly bouquet of wildflowers.

“For me?” She blushed pink beneath her matte foundation, and he nodded shyly. “Please call me Alice.”

“I’ve been so lonely, Alice, since my wife passed on.” Mildred kicked him in the shins without effect.

“I’m a widow myself.” She batted her black-lined eyes.

“Black widow’s more like it,” Mildred observed.

“Would you care to replace my wife?” Stiffly he dropped to one knee.

“You treasonous twit!” Mildred shouted, which sounded like a butterfly’s sigh. “You’re still wearing our ring.”

Alice extended her sturdy hand. “I’ll get in touch just as soon as this mutiny’s over.”

“That’s OK. I’ve got all the time in the world.”

Mildred slapped him, whisking right through his cheek, and Algernon scowled.

“What is it?” the director demanded.

“I dunno, a strange smell here like an unburied body. I should know, I had a hand in the greatest war.”

Mildred fled, her legs jerking along. One felt much shorter. Had she lost a foot on the stairs? Limping down Peppermint Lane, she wondered, do I need a siesta? I’ll lie down at home, once I’ve seen what Frank is up to with that nurse.

Angelina-O emerged from the Shipleys’ rowhouse, carrying Algy’s china dachshund.

“Pilfering,” Mildred exclaimed. “She’ll probably sell it to buy more junk.” Slipping through Frank’s door, she found him lying on the rug in his pajama bottoms.

“Frank, what’s the matter?”

“Is that you, Milly?”

“You can hear me? You’re the only one.”

“I told you, I was a jazz musician.” He grinned up at her dreamily.

“Now I’m blind.”

“I’m dead.”

He chuckled. “That’s a new one.”

“There’s a glass of water on your table. Can you reach it?”

“Can’t you hand it to me?”

“I can’t pick it up.”

“You are in bad shape, Milly.”

“How could the nurse leave you like this?”

“She got what she wanted: chocolate bars. That’s what they want, not food for their souls. Nougat bars.”

“What do you mean?”

“If we’re well, we should get sick, so they can feed us their medicine…” He winked at her and gave a rattling gasp.

“Frank,” she shouted, like a swishing curtain. A manicopter throbbed overhead. She smelled a sweet odor, like stewed prunes, and stretched out on the balding shag.

#

“She’s paralyzed,” the director observed. “Probably an allergic reaction to the sweets you tucked into her food.”

“I’m sorry,”Algernon moaned. “Our sector nurse assured me…”

“You’re not to blame, Mr. Shipley.”

“Will she ever get better again?”

The director patted his soft arm. “Don’t worry, we’ll take care of her, under your permanent allocation.” She glanced at Mildred, and then turned her back on the medical silo’s stacks of hammocks, and their jungle of intravenous lines, stomach tubes and monitors.

Algernon stopped by the man lodged next to Mildred. “Frank Zell. That’s nice; like old times.”

Frank muttered something, and his swollen eyelids flickered.

“Old Frank just made some kind of a noise. Will my wife ever speak to me again?”

“No. We had to give her a bit of surgery.”

“Was that really necessary? I don’t recall giving you permission.”

“We’re only trying to help you. With her vocal chords out she can breathe better prone.” Taking his elbow, the director guided him towards the exit.

“Well then,” said Algernon brightly. “I guess that’s quite all right.”

END

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A.K. Sykora has been an attorney in New York and teacher of English in Germany, where she resides with her patient husband and three enormous Forest Cats.

To date she has placed 50 tales in the small press or on the web, most recently with *Strange, Weird and Wonderful* (where she will be Featured Writer for Winter 2010), *Wild Violet,* *M-Brane SF,* *Rosebud* (excerpt of her humorous novel, the *Ballad of Calamity Mom*), the *Barbaric Yawp,* *Everyday Weirdness,* *the *Iconoclast,* *Skive,**Black Petals* and *Afterburn SF.* She has also placed 86 poems, and is *Green Rock’s* featured lyrical poet for June.